“If ever an instrument belonged to the lower strata of society, the cornett did. They were the poor white trash among musical instruments. Not only were they cheaply made, but they were noted for their poverty of musical qualities. Constructed of wood and covered with leather their tone was colorless, coarse and windy. Anyone with a pocketknife, a pot of glue and a thin skiver of leather could make one of these instruments... The tone was dull and windy, but for some strange reason it became extremely popular. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries it became the most popular wind instrument in Europe.”

--from H.W. Schwarz' The Story of Musical Instruments, 1938

This startling description of the cornetto comes from a book on musical instruments from the 1930’s. Though there were certainly better informed voices about at the time, Schwarz’ trashing of the cornetto perfectly illustrates the effect that obsolescence has on an instrument’s reputation. At the height of its popularity, the cornetto was the king of instruments, played by highly-paid virtuosi whose performances left chroniclers breathless with praise. Why, then, did the instruments die out, and when exactly did this happen?

The late sixteenth century was the cornetto's golden age, nowhere more so than in Venice where the leading player was the Udinese master, Girolamo dalla Casa. In his division manual, Il vero modo di diminuir, dalla Casa explains that the superiority of his instrument lies in its ability to imitate the human voice:

Of all the wind instruments, the most excellent is the cornett for it imitates the human voice more than the others. This instrument is played piano and forte and in every sort of tonality, just like the voice.

One of those who must have known and heard dalla Casa personally was the Bolognese theorist Giovanni Maria Artusi, best known for his disagreement with Monteverdi concerning the merits of "modern" music. Artusi had a high regard for the cornetto and for those who played it well:

Truly it is a difficult instrument, requiring much effort and long study. However, a single part on it can give much delight if the player has a certain excellence, as did the "Cavaliero del Cornetto" in his prime, and Maestro Girolamo from Udine, in the city of Venice, together with so many others who have flourished in this, our Italy.

The "Cavaliere del Cornetto" mentioned by Artusi is almost certainly the Cavaliere Luigi del Cornetto of Ancona praised so glowingly by Vincenzo Giustiniani in 1628:

There are, moreover, many players of others instruments, which I will not name, except for the Cavaliere Luigi del Cornetto of Ancona, who played it [the cornett] in one of my little rooms with a harpsichord which was completely closed and could barely be heard; and he played the cornett with such moderation and correctness that it astonished many music-loving gentlemen who were present, because the sound of the cornett did not exceed that of the harpsichord.

The very amazement of these gentlemen, of course, suggests that they had more often heard the cornetto played with less "moderation and correctness." Indeed Monteverdi, who had certainly heard the best musicians of his time, seems to have held the view that cornetti and trombones belonged among the less refined instruments. While discussing in one of his letters the problems of setting a certain maritime text, he protests that, "the proper imitation of the text should depend in my view on wind instruments, rather than on the more refined strings. I am sure that the sounds appropriate to the tritons and other sea creatures should be entrusted to trombones and cornetts rather than to citterns, harpsichords, and harps, since this is a maritime performance and thus takes place outside the city... So the sounds and the instruments will be either elegant and inappropriate or appropriate and inelegant". Vincenzo Galilei even informs us, with some hyperbole, that cornetti and trombones were never heard in princely chambers:

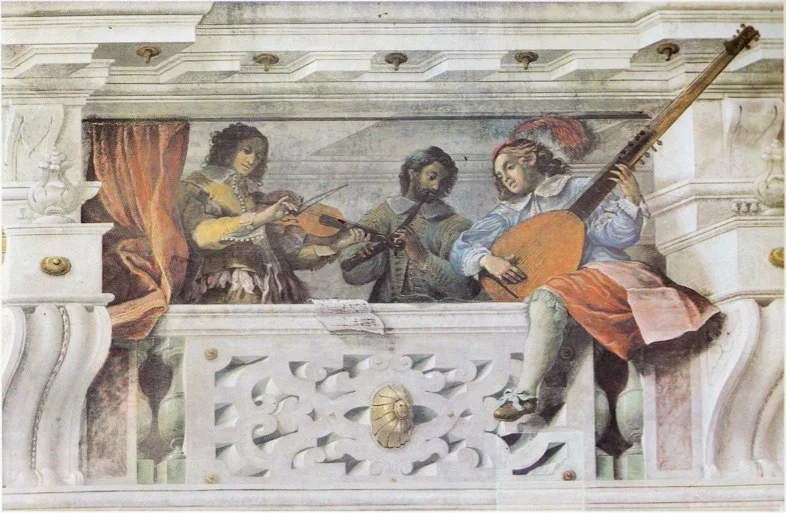

[Cornetts and trombones] are often heard in masquerades, on stage, on the balconies of public squares for the satisfaction of the citizens and common people, and, contrary to all that is proper, in the choirs and with the organs of sacred temples on solemn feast days;... these instruments are never heard in the private chambers of judicious gentlemen, lords and princes, where only those [musicians] take part whose judgement, taste and hearing are unsullied; for from such rooms [these instruments] are totally prohibited.

Players like the Cavaliere del Cornetto and Girolamo dalla Casa were, no doubt, always exceptional, even in Venice. But by 1640 cornetto playing had declined (largely because of the plague of 1630) to a point where the Procuratori of St. Mark's found it necessary to take action, stating that the cornetto had been absent for some time not only from the musical chapel of St. Mark's but indeed from all the churches of Venice. Wishing to revive this instrument "which used to give much grace to the harmony", the Procuratori decided to offer stipends to two members of the chapel, the singer Marco Coradini and the instrumentalist Pietro Furlan, to encourage them to practice the cornetto. This first attempt seems to have failed, for the Procuratori tried again in 1643, arranging for Marco Pellegrini, a violinist in the chapel, to teach the cornetto to two young students. They were both accepted in the chapel within two years, their short period of training indicating, however, that the tasks demanded of them were not overly difficult. The days of brilliant cornetto virtuosi at St. Mark's were clearly gone.

Despite these difficulties, the cornetto managed to maintain a place in the chapel at St. Mark's until after 1714. In Bologna, another center of cornetto playing, the instrument seems to have flourished somewhat longer. Difficult cornetto parts turn up occasionally in the latter half of the 17th century in the works of local composers including Francesco Passarini and Maurizio Cazzati, although it is worth noting that it was Cazzati himself who brutally re-organized the musical chapel of S. Petronio in 1657, letting go en masse all the cornettists and trombonists, some of whom had given 30 or 40 years of service. They were replaced with violins and violoncelli.

Bologna also possessed one of the most famous ensembles of cornetti and trombones in Italy, the Concerto Palatino della Signoria di Bologna. This ensemble existed for more than 250 years, usually in a formation of 4 cornetti and 4 trombones, and was not disbanded until 1779. By this time standards on the cornetto had sunk so low that the city fathers voted to silence the Concerto Palatino, setting forth there reasons in the following deliberation:

As long as there were to be found, among the musicians of this illustrious and exalted Magistrate, individuals capable of playing the cornetts in at least a tolerable manner, especially in the sacred functions in which the superiors take part, the principle of preserving the said concerto was faithfully followed, out of respect for its antique origins and in order not to gainsay a popular tradition which the exalted Magistrate must acknowledge as stemming from the munificence of Charles V. But either the great difficulty of adapting the said cornetts, very imperfect in their structure, to the harmonious expression of that kind of music which corresponds to the genius of the present time, or the scarceness of subjects in possession of the natural disposition necessary to take on and cultivate the sound of this instrument, actually out of use, has made manifestly clear the absolute necessity of substituting the cornetts with some other instrument more grateful to the ear and which might remove the unpleasantness which results from hearing, in the public functions and, above all, in the churches, a very disagreeable dissonance, from which derives a manifest scandal.

In England, the Restoration and the ensuing change of fashion at court dealt the death blow to the cornetto. Soon after his coronation, Charles II set about re-organizing the "King's Musik" along French lines. John Evelyn bears witness to the effect of this change on the fortunes of the cornetto:

The 21st [December, 1662], one of his Majesty's chaplains preached, after which instead of the ancient, grave and solemn wind music accompanying the organ, there was introduced a consort of twenty-four violins, after the fantastical light way of the French - better suiting a tavern or playhouse than a church. This was the first time of the change, and now we heard no more the cornett, which gave life to the organ, for that instrument, in which the English were so skillful, was quite left off.

Probably the cornetto was not entirely "left off", as Evelyn puts it, much before 1700, though standards had surely slipped by the time Roger North writes in 1695 that, "nothing comes so near or rather imitates so much an excellent voice as a cornett pipe, but the labor of the lips is too great and it is seldom well sounded."

The cornetto survived longer in northern countries than in the south. After 1600 a striking influx of Italian musicians into Germany created a great flowering of cornetto playing there which lasted through most of the 17th century. By 1700, however, the cornetto was definitely regarded as old-fashioned, though it continued to be played, particularly by church musicians and Stadtpfeiffer, for a remarkably long time. More and more, though, the instrument was no longer the province of professional virtuosi, but of humble town musicians. Mattheson writes, in his Neueroeffneten Orchester (1713), that, "the slight use of this instrument nowadays does not merit that anyone particularly apply himself to it anymore and so waste his breath in this activity. In the churches the cornetts still hold out now and then, but otherwise they are seldom to be seen." Where cornetti were heard, they are described as loud, rather rough instruments played with tremendous effort. Joseph Majer's comment in 1732 is typical:

The "hard" cornett ... is extremely difficult, indeed the most difficult of all the wind instruments, and sounds, from far away, like a raw, unpolished human voice.

To the author of the Grosses vollstaendiges Universal Lexicon (1733) the instrument seemed so demanding that "the difficulty of playing it has presumably brought it out of usage here."

Still further to the north, in Norway, the cornetto enjoyed an even later flowering. In 1744, the German-immigrant Stadtpfeiffer and organist Johann Daniel Berlin published, in Trontheim, a treatise on the instruments in which he speaks of the cornetto:

The cornett ... is generally used in loud and splendid music, and accompanied by or together with trombones; it is employed on the highest part when there is no soprano trombone. However, even in such a case, one still prefers the cornett to the soprano trombone, because the cornett can play with graces... One will find only a few who can manage to play the cornett well. The reason is that great strength is required to meet the demands of the cornett properly; many thus find it extremely difficult.

Apparently Berlin did find some players who could manage the instrument exceedingly well, for a sinfonia by Berlin for cornetto and strings, in a manuscript in Trontheim, is extremely demanding on the player, who must play to the very top of the instrument's range and negotiate difficult leaps in a thoroughly Rococo manner.

The cornetto was still heard in Norway in 1782 as Lorents Nicolaj Berg relates in his Den frste Prbe for Begundere ude Instrumental-Kunsten:

This instrument is not very well known except among musicians. Only very rarely does one get to hear a cornettist. I myself have only heard one who knew how to play this instrument well: a musician-journeyman who, like myself, was serving with the city musicians in Copenhagen. It is used in church music, together with trombones, for chorales, etc. That is a magnificent kind of music, and the cornett can also be heard over a full organ. On the cornett one plays the melody; it has a great similarity to a strong penetrating human voice.

The image of a simple village musician blowing, obviously very hard, on his cornetto is captured amusingly by Berg in an anecdote he says was well known at the time:

Once upon a time a farmer in the city saw somebody playing on a cornett, and in telling his neighbor some of the things he had seen, he said:

Some were blowing with their cheeks on a rod,

Another was biting on a sausage which was 7 quarter long,

He was biting pieces out of the sausage,

I truly believe the sausage was very hot,

For his fingers went up and down every time he bit,

And his eyes were popping out like stones.

We have come a long way from the Cavaliere del Cornetto to this musician blowing on his "sausage", but, we are certainly nearer to Schwarz' "poor white trash among musical instruments." As an instrument of the Stadtpfeiffer, played in all likelihood ever more poorly, the cornetto lasted until at least 1840, when Jean Georges Kastner, the French composer and musicologist, heard one in Stuttgart:

In 1840, while I was in Stuttgart, I heard every day a concert of religious music performed by four musicians who, according to the practice, climbed to the balcony of the tower to play a chorale, of which the first voice was played by the "zinke", and the others by alto, tenor, and bass trombones.

Kastner, being well acquainted with earlier descriptions of the cornetto, was, like Schwarz, at a loss to understand the instrument's former glory. The "most excellent of wind instruments" had fallen on hard times.

©Bruce Dickey, 2009